I saw the following chart in an issue of Peak Oil Review, a publication about the oil industry.

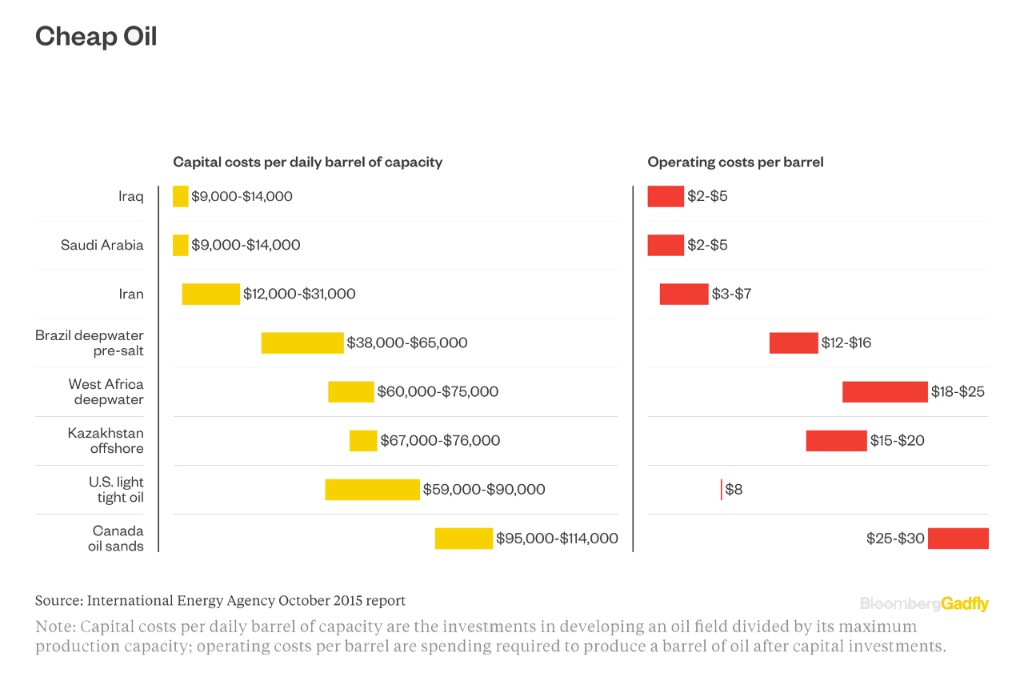

Note the numbers on “U.S. light tight oil.” This is what we would call fracked oil, that is, oil from one of the shale deposits in the U.S. What distinguishes these deposits is the difficulty of extracting oil from them. They have low permeability; the gaps in the shale are small and not well connected, so there isn’t much oil per cubic meter and that oil has a tough time moving through the rock. Just for comparison, sandstone oil deposits in Saudi Arabia have a permeability of about 5 Darcies. (A Darcy being an oil industry specific unit of permeability and perhaps 19th century English hunkiness) An American shale deposit might have a permeability of 5 milliDarcies, one-thousandth as much.

The answers to these problems are horizontal drilling (“bottle brush” wells) and hydrofracturing, the injection of high pressure fluid to crack open the shale. These are expensive processes.

Note that in the chart the capital costs are per peak daily barrel, not the average. Because of the nature of a fracked well, the output tends to be extremely high at first, but tapering off quickly. A fracked well might produce most of its total output in the first few years of production. In contrast, a conventional oil field in the Middle East might slowly develop to peak production and last decades. Note the relatively low capital and production costs for Iraq and Saudi Arabia.

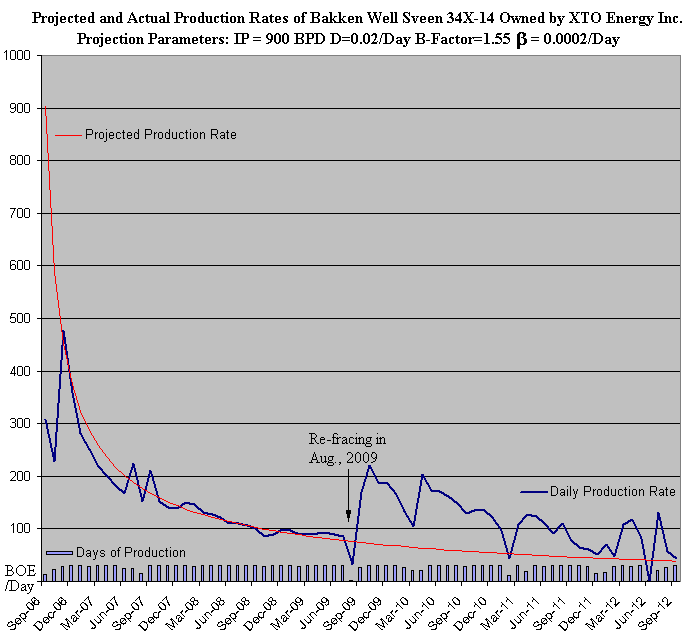

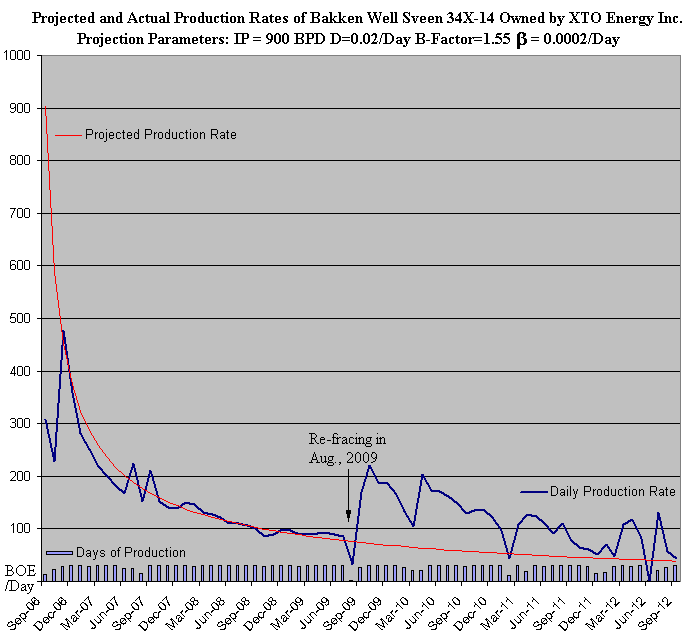

Elsewhere, on an investment site called Seeking Alpha I found a graph of projected and actual production from a particular well drilled in the Bakken shale formation in eastern Montana and western North Dakota.

Looking at these numbers it strikes me that the pessimism I hear about the economic viability of these shale formations is well founded. I’ll apply the numbers from one to the other to get a general idea of the economics. Right now crude oil is around $57/barrel. Subtract the $8/barrel for production costs and the oil producer will have $49/bbl to work with.

The well in question peaks at about 475 barrels per day. By the EIA chart, a 475 bpd well costs between $28 million and $42.75 million to drill. The average over six years is about 1/3 of peak, so drilling costs $180,000 to $270,000 per average daily production.

At $49/bbl, $180k/$49 = 3673 days to breakeven, or about 10 years. The higher number, $270k, gives a breakeven point of 15 years. Add interest payments to that.

Right now those millions are coming in the form of junk bonds and venture capital. The bonds pay around 5-7% interest. The investors want higher returns, but I’ll be optimistic and assume 5%. At the low end that starts off with interest payments of $1.4 million/year, which is $3835/day or 78 barrels breakeven at $49/bbl.

Eyeballing at the production graph, the first 3 years average 150 bpd so the well makes $2.68 million/year, netting about $1.3 million/year. Problem: If the loan period is ten years, then annual interest and principal would total $3.64 million. This well could make that in the first year, but not the second.

Note that the producers re-fracked the well when it dropped below 100 bbl/day. Re-fracking costs about $2 million and brings it back to 100-200 bbl/day range for a couple of years. With an average over the next few years of a bit over 100 bbl/day, this adds a year to the breakeven point.

At the end of six years the flow has dropped to around 50 bbl/day. Even if the production company had somehow been making full payments all along, this is still something close to the breakeven point for just paying the interest (~$890k). There are at least five more years to go before the well makes back its initial investment.

This is all generalities, averages, and back-of-the-envelope, but even with a more optimistic scenario it doesn’t look good for the loan officer who approved this one. The operators will struggle to eke out sufficient total production and will probably hit permanently negative cash flow just two years in.

Not all sections of the various shale fields are the same. There is a concentrated area of low cost wells in a few western counties of North Dakota. These wells can make money at $40/barrel. On average, though, shale oil is a losing proposition in the mid-fifties. The average breakeven price is more like $60, and shale oil in the U.S. suffers from price discounts due to inadequate transportation infrastructure. Conoco Phillips, the largest U.S. oil exploration company, has announced that it will not pursue any opportunities with all-in production costs of over $50/barrel. That limits their options.

As recently as the summer of 2014 the WTI oil price was over $100. A combination of U.S. and OPEC overproduction killed the price. U.S. shale oil production went from 1 million barrels/day in 2007 to a peak of just over 5 million in 2015. It has dropped by a million since then, but OPEC is holding back production to keep the price in the $55-$60 range. They can crash the price again if they think wiping out U.S. shale production is in their interests. Then again, if they manage to crank the price over $60 fools will rush in and complete half done shale wells and the overproduction will drop the price again.

Witness the string of bankruptcies in the shale oil and gas sector. There were 89 last year alone. Investment has dropped off and the rate of new wells being drilled is down. Most of the major players are burning at least $500 million annually.

I know you will be shocked, shocked, by this, but it looks as if the shale oil boom was mostly a con from the beginning. It efficiently transferred cash from the pockets of investors, banks, and bondholders into the pockets of drillers and oil service companies. It was less efficient at transferring oil out of the ground for less than the market price.

Friday, August 13, 2021 at 2:49PM

Friday, August 13, 2021 at 2:49PM